Listen to the audio version. This essay is also available as a podcast.

I was walking this morning in the falling snow — the flakes like ash against the flat grey sky — reflecting on FREE SCHOOL and the bridges I burned when I “burned it all down,” and a thought began to flicker:

“Some branding expert you are! If you were so good at branding, then you wouldn’t have lost so many people in your audience.

The goal of branding is to cultivate loyalty and you failed.

Your audience was disloyal. You alienated them. They felt betrayed and they left you. How embarrassing.”

I walked with this thought and allowed myself to be curious about it. (Instead of panic heaving into my scarf. Healing, amirite?!)

It reminded me of a talk I gave right before the burning, where I received the following feedback:

“RKA was great, but I didn’t really know where she was taking me…?”

Needless to say, I did not make a loyalist out of that person.

Another fail?

Your typical branding and marketing strategist would look at this as a problem to be solved.

As StoryBrand scheme man Donald Miller says:

“If you confuse, you'll lose.”

(Hey Don, I’m still confused about this. But I digress…)

The riches are in the niches, "they" say.

And to claim those riches, you must be willing and able to boil down your business into a tight little tagline that tells people exactly what they can depend on you for, no matter what.

If your audience can’t easily tell where you’re leading them in a few seconds of glancing at your website — or in the opening minutes of your talk, in this case — say goodbye to the riches, bitches.

Back to my inner monologue:

"If the goal of branding is loyalty, can I really call myself a strategist? After I pushed so many people away? Lost so many people in my audience? Gave a middle finger to prevailing marketing wisdom and my audience’s understanding of me, leaving them feeling confused and betrayed? I lost their loyalty. I became unforgettable in the worst ways."

I wrestle with these questions every time I show up online, outside of the box I formerly fit so neatly inside.

When I share a serious poem on a feed that is often filled with laughter.

When I pen an angry missive after years of cloaking my frustration in comedy.

When I do anything at all that doesn’t reinforce a tagline I wrote years ago.

In my last email, I wrote that branding, marketing, and online business need more activists.

What does it mean to walk the tightrope between activism and branding? To run a business in today’s crumbling capitalist infrastructure — needing to feed ourselves while also living our values?

Maybe it means to “betray” our audiences and their expectations of us.

Maybe it means to divorce our industry’s hyperfixation on “brand loyalty” at any cost.

Because, how exactly do you achieve brand loyalty? Propaganda.

It’s fitting that one of the most famous names in the branding game today is Donald Miller, a religious leader turned marketing minister.

The leap from proselytizing to propagandizing, from converting sinners to converting subscribers, is consistent with the history of the advertising industry.

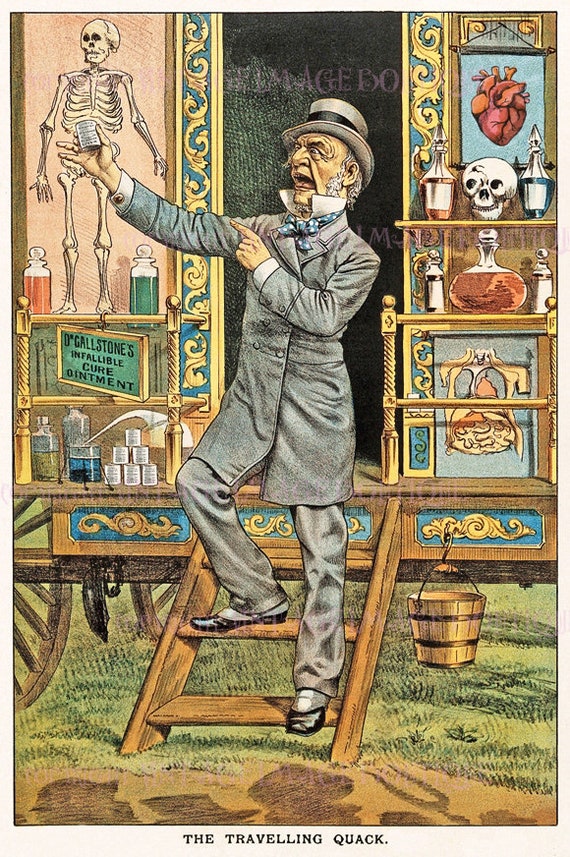

Many of the early “scheme men” (yes, that is what advertisers were referred to as in the 19th century) were former preachers who saw how their skills for storytelling could be used in more lucrative ways.

The word “propaganda” itself comes from the Catholic Church and means “to propagate the faith.”

Before capitalism, the church was the only institution that used messaging to influence the masses at scale.

The goal was to cultivate widespread loyalty (or “fidelity”) to the church above all else.

This shifted in the 19th century with the advent of mass production.

Those products needed buyers — loyal ones, at that, to keep the wheels of our newly industrialized society turning.

Enter a new type of propaganda. The commercial kind.

Like the church, this propaganda asked folks to have faith in a faceless company, something they couldn’t see with their eyes, but were promised through words on a page (and in some cases, the impassioned sermons of the company clergy, i.e. its salesmen.)

Why do I call it “propaganda” instead of advertising?

The secular definition of propaganda is the systematic dissemination of information (whether true or not) to influence public opinion.

Academics and advertising apologists often try to separate marketing from propaganda by emphasizing how advertising aims to sell products and services, while propaganda aims to influence public opinion, in order to further a cause or biased agenda.

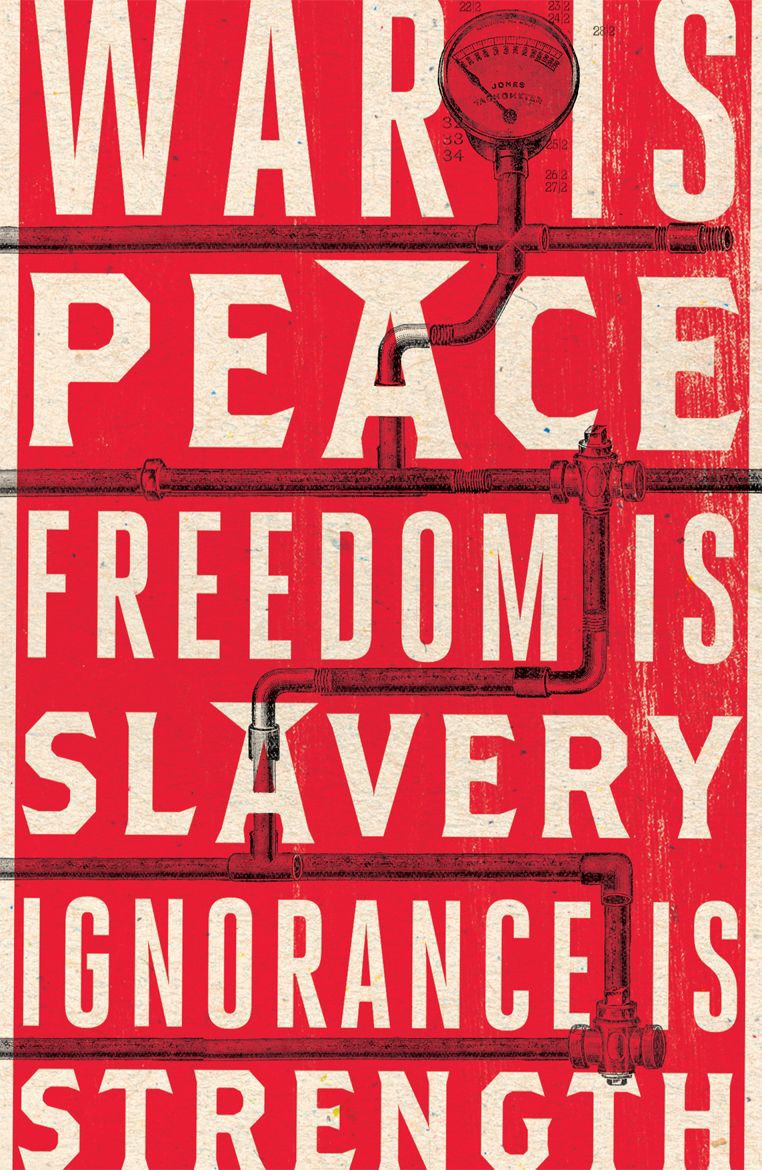

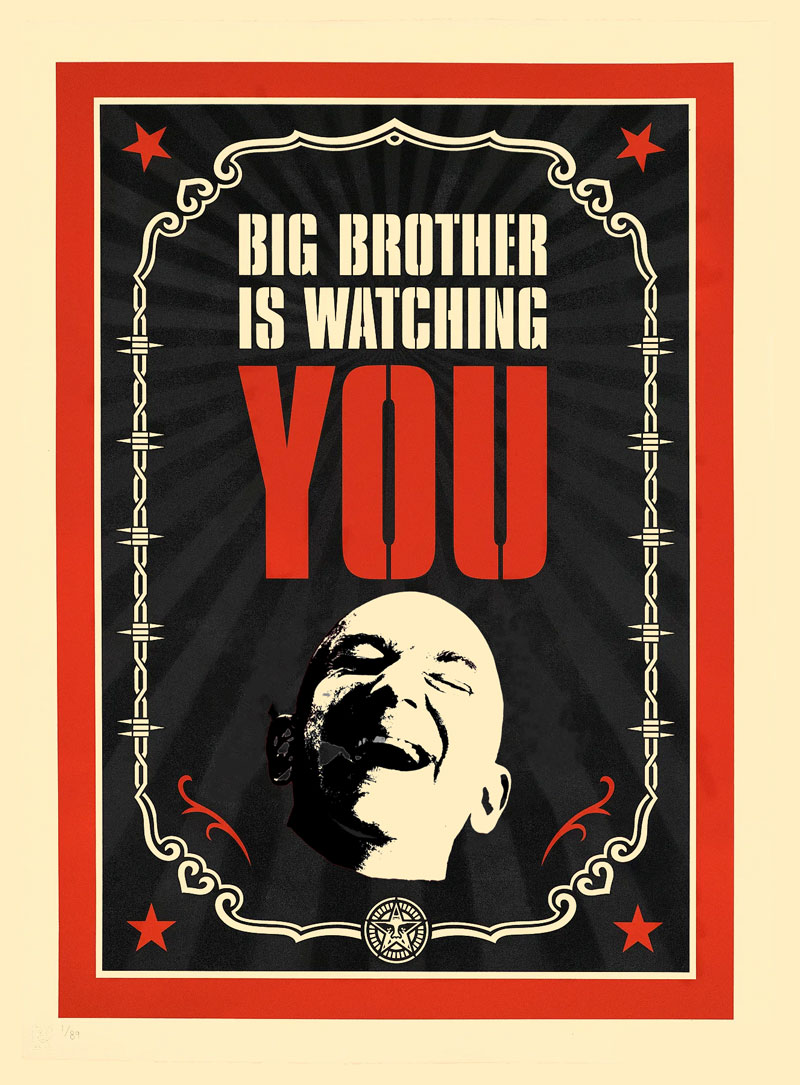

But I think that’s what George Orwell called “doublespeak” in his dystopian 1984 — language that deliberately obscures, disguises, distorts, or reverses the meaning of words.

Branding is the bridge connecting advertising and propaganda.

Because while an advertisement itself may “innocently” promote a product, each ad does its duty in service to branding, i.e. influencing public opinion in order to further that company’s agenda of loyalty above all else.

Back to my earlier question: “How exactly do you achieve brand loyalty?”

Through propaganda designed to advance the agenda that our customers can depend on us, no matter what.

That we will not change and they can count on that.

Or that we will only innovate in ways they expect and desire us to.

People change. People disappoint. And those same people will spend lots of money with brands that best sell the illusion of a dependability you simply can’t get from human beings.

Fun fact: the word “dependability” itself was manufactured in the early 20th century by Theodore MacManus while branding Dodge Motors.

In that early pursuit of a customer’s brand loyalty, advertising “scheme men” pushed the agenda that brands can do better than humans can, which also happens to be the case for capitalism and consumer society, in general.

But this thinking had to be trained into us.

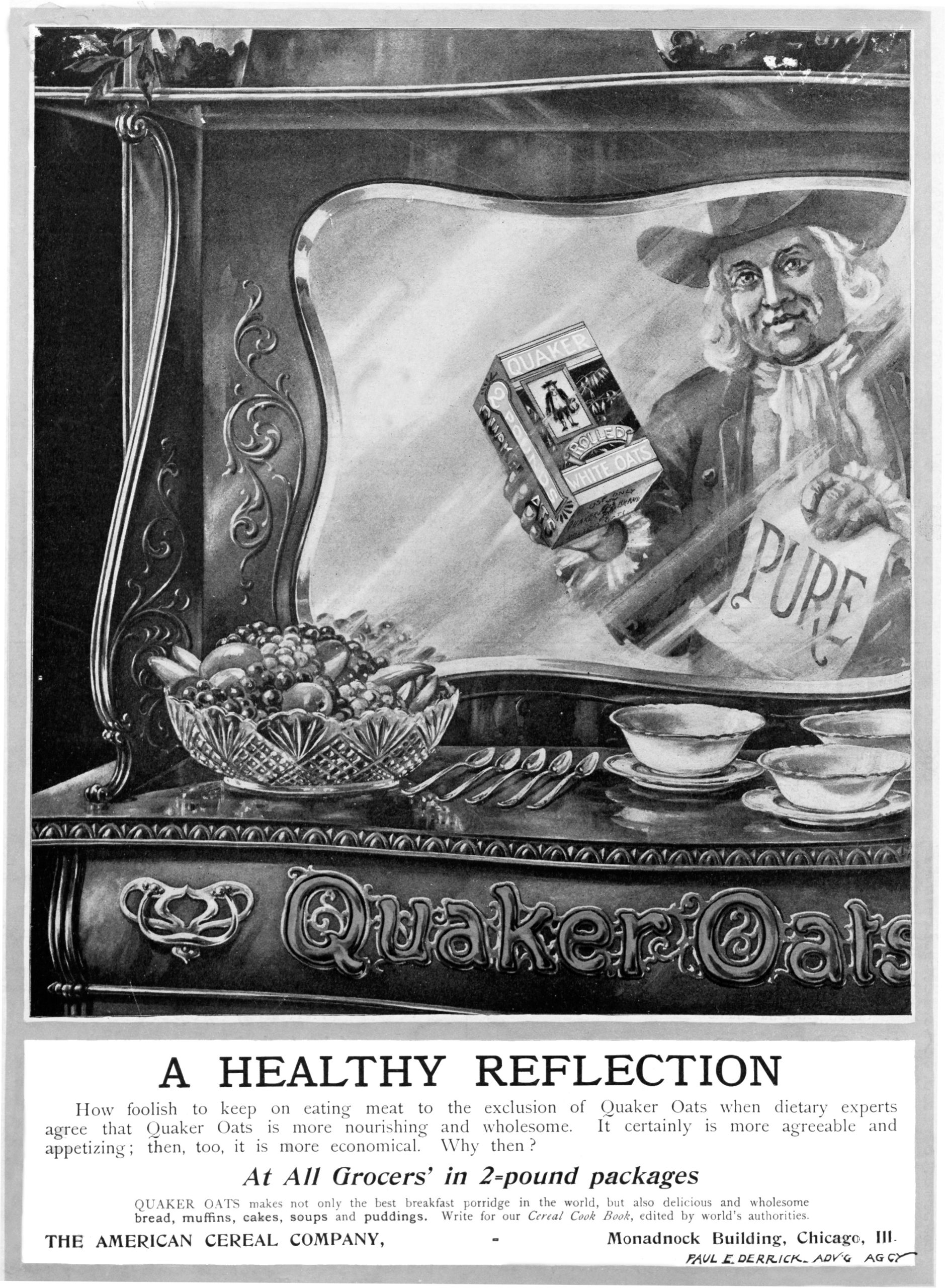

Remember! Before the existence of brands — and the mass production they rode in on — people bought from people.

We didn’t buy our oats from a Quaker faker. We bought them from Gus at the general store, who scooped our grains out of an unbranded barrel. The riches were not in the niches for those shopkeepers. Various & sundry was the name of the game.

It didn’t come naturally to us to pivot to buying from the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker, who we knew by name, to faceless companies. We were skeptical. (For good reason.)

Enter branding.

Not only did early branding help unknown companies create a sense of intimacy with customers so we would “know, like, trust” them, but it created shortcuts around the long, arduous work of building reputation.

With branding, the trust that formerly took Gus at the general store years to build could be manufactured for the Quaker faker through advertising in a matter of months.

(I call him the Quaker faker because Larry, the Quaker Oats mascot, was based on the reputation Quakers being honest and trustworthy. None of the Quaker Oats founders were actual Quakers.)

As MacManus himself, inventor of the word “dependability,” and one of the early pioneers of branding, said about his work:

“We have found a hothouse in which a good reputation can be generated, as it were, over night. In other words, the thing for which men in the past have been willing to slave and toil for a lifetime, they can now set out to achieve with semi-scientific accuracy and assurance of success, in periods of months instead of years.”

In this way, corporate branding has historically concerned itself more with manufacturing a reputation of quality vs. actually delivering on said quality.

We can see how this evolved to today's brands like Nike, who manufacture reputation but no longer manufacture any of their own products — instead outsourcing their manufacturing to the lowest bidder, which is almost always a sweatshop.

But do consumers care or even believe this to be true? No, because Nike has spent 58 years manufacturing a reputation of dependability, even while they repeatedly fail to deliver on it.

I know what you're thinking.

Okay, this sounds like a bit of a stretch, RKA. If a company produces a bad product, it earns a bad reputation and therefore, a bad brand, and people stop buying. Right? Haven’t you ever heard of cancel culture? C’mon.

You’d think so.

And, just as you'd expect, early branding efforts faced this exact problem. Thanks, in no small part, to the undependable human nature of the snake oil scoundrels and “scheme men” making outrageous claims of their product’s ability to cure all ails, while ultimately worsening their customers’ problems.

Yes, those conmen got “cancelled” by the scorned public. This led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration and a messy reputation for the fledgling advertising industry.

Branding was over before it even began.

Until a new kind of propaganda came on the scene.

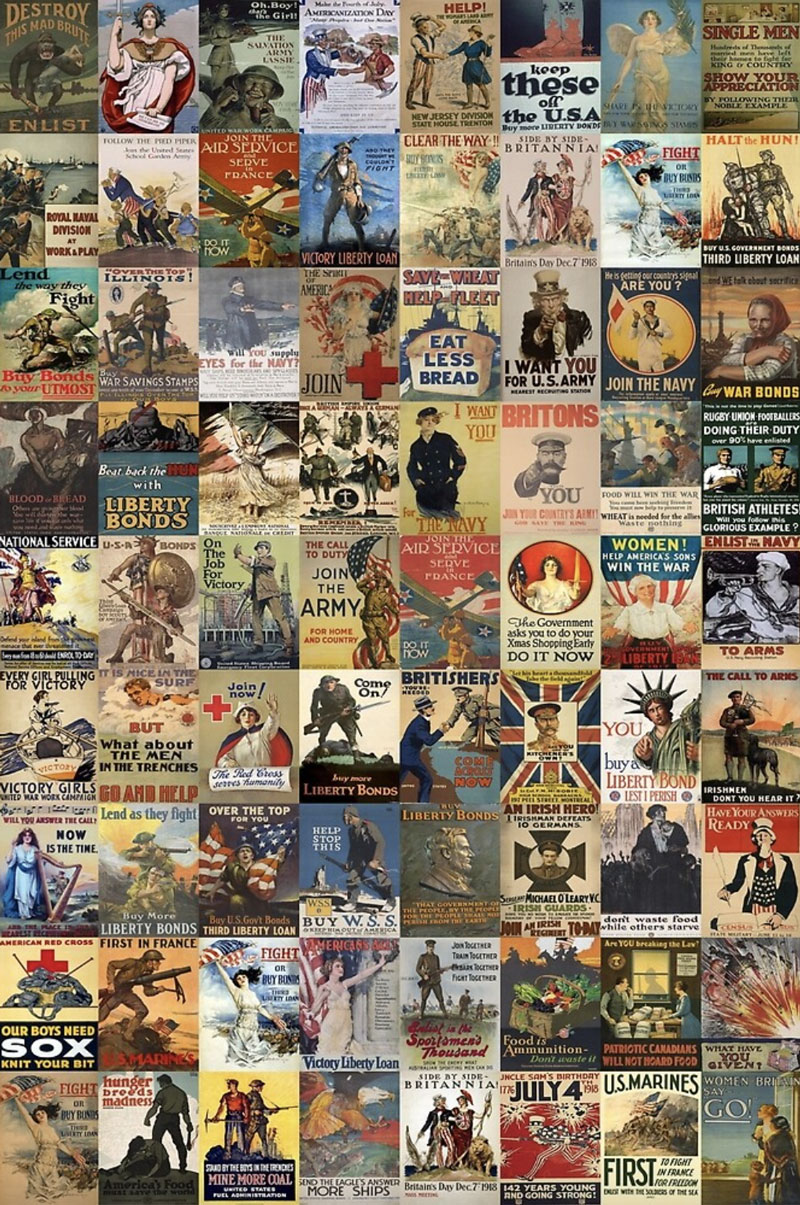

Branding as we know it today owes its existence to World War I propaganda.

More specifically, the efforts in both England and the USA to shape public opinion so they could entice a steady stream of willing war volunteers to enter the fray — despite all the odds being against them — and ensure the public supported their sacrifice.

Before WWI, advertising as an industry was on shaky ground. The "cure-all" patent medicine claims of snake oil scheme men generated widespread public backlash and a lasting skepticism about the value of advertising.

Then came the war.

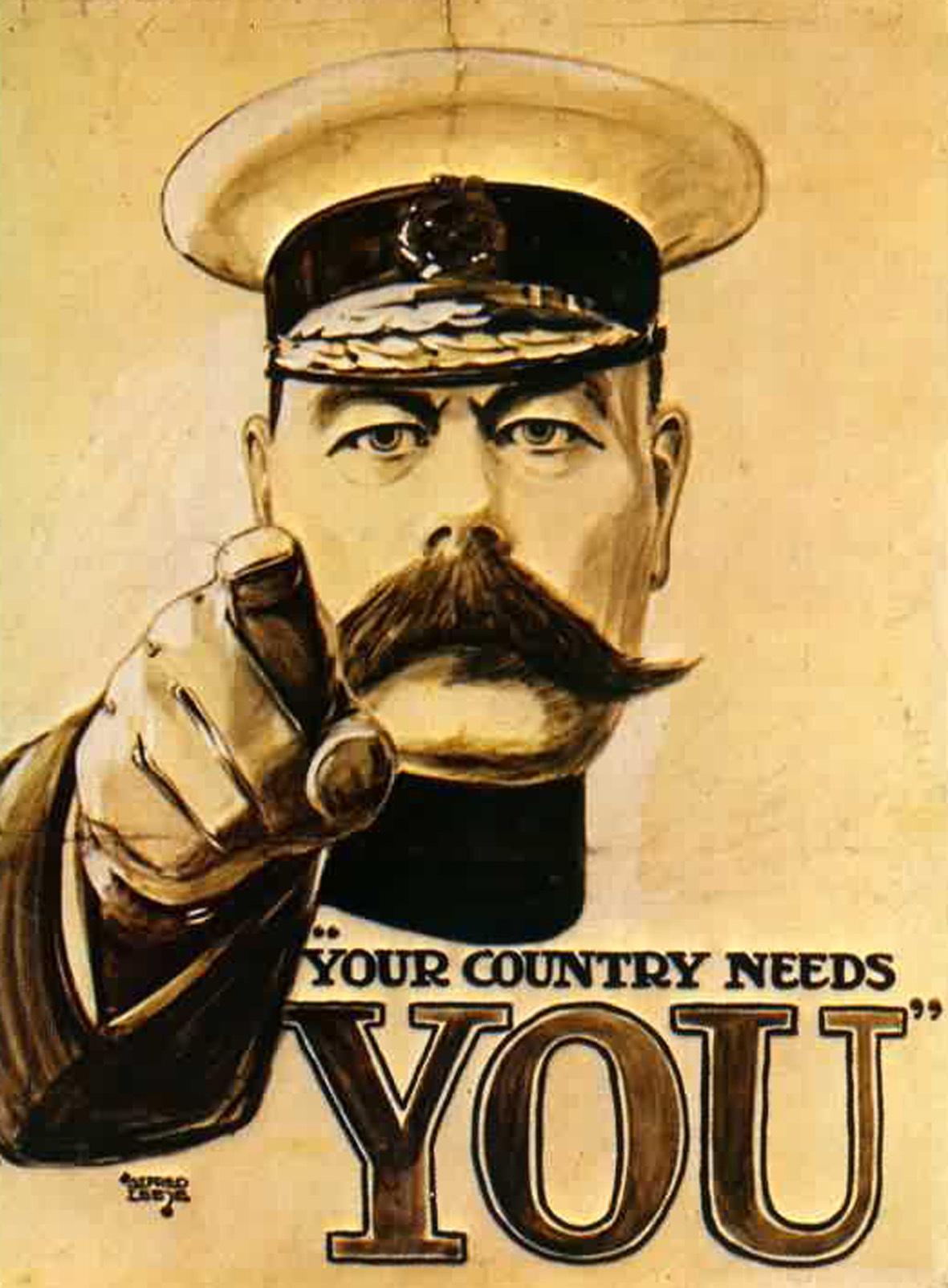

The British needed volunteers and Lord Herbert Kitchener had a brand new idea for moving them to enlist — he’d appeal to their emotions through the “first systematic propaganda campaign directed at the civilian population.”¹

Kitchener’s face and finger wallpapered Great Britain with his call of duty: “Your country needs you.”

This was the first time a government had communicated with its citizens in this way, both in terms of scale and the approach of directly pulling on their heartstrings and their sense of brand/national loyalty.

And it worked. Over two and a half million men volunteered for war, despite a roughly 50/50 chance of dying or being seriously injured in battle.

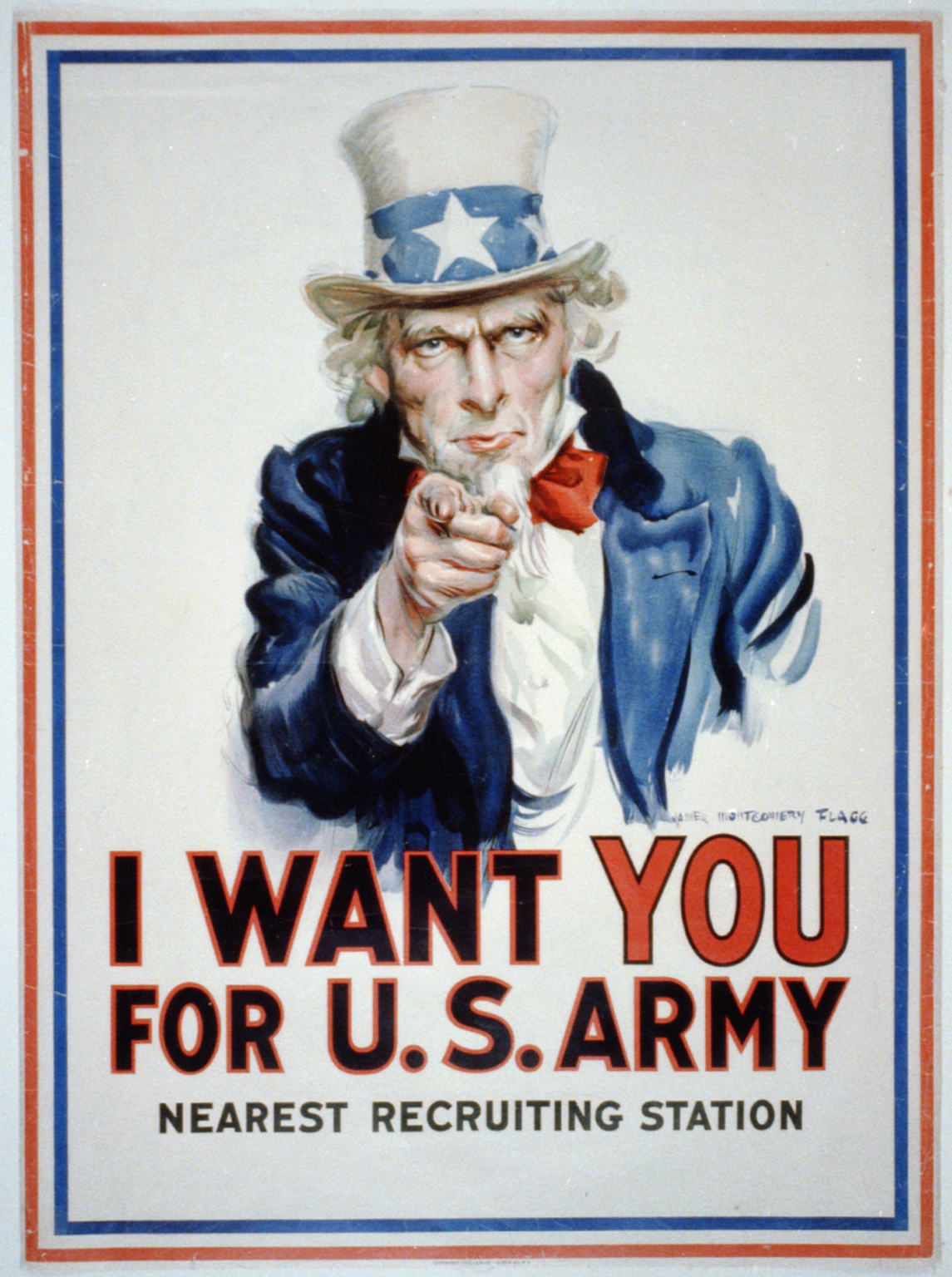

When it came time for Woodrow Wilson to break his campaign promise and send U.S. civilians to war, he did what Americans do best — looked to what was working overseas and copied those methods, supersizing them.

He instituted the Committee on Public Information to do what Kitchener did, but he swapped British restraint with American pomp and circumstance.

The goal of the Committee on Public Information was to systematically squeeze out any hint of dissent.

Just as brands today manufacture reputation, the Committee on Public Information manufactured public opinion through omnipresence.

To quote George Creel, the head of the Committee, there was:

“...no medium of appeal that we did not employ. The printed word, the spoken word, the motion picture, the telegraph, the cable, the wireless, the poster, the signboard — all these were used in our campaign to make our own people and all other peoples understand the causes that compelled America to take arms.”

I can't help but notice the eerie similarity between Creel's description of shaping American public opinion and the way Orwell describes The Ministry of Truth systematically rewriting history in 1984:

“This process of continuous alteration was applied not only to newspapers, but to books, periodicals, pamphlets, posters, leaflets, films, sound-tracks, cartooons, photographs — to every kind of literature or documentation which might conceivably hold any political or ideological significance.”

In his book, How We Advertised America, Creel explains:

“What we had to have was no mere surface unity, but a passionate belief in the justice of America's cause that should weld the people of the United States into one white-hot mass instinct with fraternity, devotion, courage, and deathless determination.”

Creel’s campaign was so successful, it not only resulted in unified public opinion, it rescued advertising’s reputation.

Coming off WWI, the business leaders and their customers, who formerly snubbed their collective noses at mass advertising campaigns, saw just how potent mass propaganda could be.

They were converted.

You know who else got excited about the power of propaganda to shape public opinion? Adolf Hitler. He took notes. And applied them.

And so did Russell Brunson, half a century later.

Brunson, the founder of the ClickFunnels marketing software, is one of the most famous and successful “scheme men” of our modern day.

And Brunson proudly cites Hitler, who he compares to Jesus Christ, as the inspiration behind his book Expert Secrets on how to build a cult following of people who will do anything you ask. Go fuck yourself, Russell Brunson!

Back to World War I...

America was the brand. Creel and his Committee needed to cultivate loyalty.

And, as Creel himself describes in How We Advertised America, the quest for brand loyalty is the quest to override our audience’s intellectual curiosity, their observations, reasoning, and logic, and compel them to make decisions based on emotions, first and foremost.

After WWI there emerged two main viewpoints on propaganda:

1. Terror

People like Louis Brandeis, Supreme Court Justice and passionate defender of the First Amendment, believed that propaganda was an enemy of free speech and, with it, the “pursuit of happiness” that America supposedly enshrined. Brandeis equated happiness and intellectual courage, which he believed could only develop in a society that put free thinking over blind loyalty and nationalism.

2. Excitement

People like Edward Bernays, often cited as "the father of public relations," who felt that the key to a functional democracy was brainwashing idiots into doing your bidding. Yeah, I'm snarking, but I’m not exactly a fan of this Freudian dickfunnel. Bernays believed that the masses couldn’t be trusted to think for themselves and needed to be guided to make the right decisions.

100 years later, I think it’s evident which side won that war.

Bernays became one of the most influential figures in advertising of all time. The nephew of Sigmund Freud, Bernays brought wartime techniques to influence the unconscious mind into the mainstream.

His campaigns included popularizing smoking in women by positioning it as a feminist act, labeling cigarettes "torches of freedom." (Thirty years later, Bernays led campaigns to inform the public of the dangers of smoking.)

In between, he helped facilitate the 1954 Guatemalan coup, on behalf of the U.S. government and the United Fruit Company (now "Chiquita"), branding United Fruit as a crusader against communism.

The overthrow of Guatemala's democratically elected president Jacobo Arbenz led to 40 years of civil war, decades of brutal occupation by U.S.-backed regimes, and the murder and disappearance of hundreds of thousands of people.

There is perhaps no greater example of Bernays's skill for spin, than how he spun his own career in this quote from a BBC interview in the '90s, which reads like a page from 1984:

“I decided that if you could use propaganda for war, you could certainly use it for peace.”

Propaganda wins because it's easy.

Just like war is easy. (Or, on a smaller scale, hitting a child, instead of actually parenting them.)

Because it doesn’t involve actual persuasion. It involves domination. Subverting another’s will, reason, and logic through violence. And in the case of propaganda, volume, and omnipresence.

This omnipresence was ultimately what made WWI propaganda so effective. It was everywhere.

Sound familiar, marketers? In the last few years, “omnichannel” advertising has been all the rage. This is why.

Brands were created to replace human beings.

Because in the era of mass production, no human being can possibly churn out the sheer volume and omnipresence of propaganda it takes to manufacture trust at scale.

Now human beings are trying to behave like brands — to be dependable, easy to understand, and everywhere at once.

To fit our selves into neat little Happy Meal shaped boxes.

What happens to the ideas, the innovations, the parts of our selves that don’t fit into the little red box — or a fifteen second TikTok?

I’m sure my former self and I disagree on all this.

I have spoken in the past about brand loyalty as the ultimate goal of marketing.

And if I wanted to stay “on brand,” I would find a way to make my former self and my current self agree.

Because, if I reveal to you that I have changed my mind — that my thinking on this topic has evolved — well, that will make my brand confusing.

It will undermine my dependability.

It will make me an unreliable narrator.

It will mean I lose your “loyalty” to me and my ideas.

And it would also mean I was lying to you. And, worse, myself. All to further my brand’s agenda of loyalty above all else.

This is what I did for a long time.

Trying to fit my every idea into a box I had long outgrown.

Trying to ensure that every piece of content or new offer I generated could coexist with the expectations I had established long ago, Donald Miller’s words ever resounding in my head:

“If you confuse, you'll lose.”

But, lose what exactly?

It's not progress or innovation or social good that Miller warns us we will lose if we confuse, but...

Money. Influence. Power.

And market logic as cosigned by Miller and today's reigning scheme men heartily endorses us overriding our customer' own logic in order to preserve those things, no matter the cost.

What is this doing to us?

What we buy?

What we sell?

What ideas we deem worthy of consuming?

What innovations we deem deserving of funding?

The questions we ask?

The answers we give?

The culture we create?

I think it's turning us into what Creel envisioned when he “advertised America”: “one white-hot mass instinct” of “deathless determination.”

Holy fuck. We colonized the planet for this bullshit?!

For Fox News? And factories full of mass-produced plastic we have to trick people into demanding? And dickrockets to space while the world burns below? And manufactured “dependability”?

For a world where, in order to keep growing, we must subvert logic and reasoning so we can manufacture trust — while we relegate actual manufacturing to whoever has the least money, influence, and power?

Does this feel like freedom to you?

Does this feel like progress?

And is this truly what’s best for our customer?

An illusion of superhuman dependability and the pursuit of loyalty, no matter what?

If we want our customers to be loyal to us above all else, then what does it mean when we change? We have to betray ourselves to stay loyal to our brands so our customers will stay loyal to us.

We are lying to our customers to advance our brand’s authoritarian agendas.

Time to be disloyal — to our own brands. To the market. And the prevailing “wisdom” that earned its status, not by merit, but by force.

Time to betray our audiences.

By being disloyal to them and their ideas of us, we give them permission to be loyal to their own logic and reasoning.

We hand them back a piece of their own autonomy.

Demanding and expecting loyalty from customers — or friends or family or partners or colleagues or, or, or, or — is the beginning of authoritarianism and abuse.

If you, like me, are walking the tightrope between branding and activism, do you want to contribute to a brand culture that normalizes unflinching loyalty, no matter the cost?

Yes, relinquishing the ease of a propagandized approach to marketing ultimately means that we, as business owners and as people, have to do the hard work of nurturing relationships day after day.

Not simply expecting that if we brand hard enough, we can expect lifelong loyalty.

Yeah, yeah, I hear you, Donald Miller:

“If you confuse, you'll lose.”

But what will we all gain?

Research for this post came from:

- ¹The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads, Tim Wu

- The Human Brand: How We Relate to People, Products, and Companies, Chris Malone, Susan T. Fiske

- How We Advertised America, George Creel

- 1984, George Orwell

- Expert Secrets, Russell Brunson

- Building a StoryBrand, Donald Miller

p.s. Sick of newsletters that have all The Answers™? Well, I've got nothing but questions. For more marketing muckraking and brand strategy gone wild, sign up for my emails here:

If you liked this, read on:

In many ways, it seems easier to become a “personal brand” version of yourself than to be yourself. Brands are built on simplicity. A “good”…

Read More...Rebrand TOO MUCH to SO MUCH. Instead of saying, “She’s TOO MUCH,” say, “She’s SO MUCH.” You’re welcome. Lessons on burning it all down…

Read More...In 2021, I started a business / art experiment called FREE SCHOOL. I didn’t know at the time that this school would teach me to free myself. What happens after you burn it all down?

Read More...