Listen to the audio version. This essay is available as a podcast!

Instagram has brought back the chronological feed.

Kinda.

They’ve hidden the feature behind the Instagram logo on the home screen; tap it and you’ll find the hidden easter egg of “Followers” and “Favorites” to return you to the halcyon days of the platform, when you saw who you wanted and weren’t dogged relentlessly by sponsored sundresses and skinny teas that’ll make you pee out your butt.

Finally! The gram is giving back to the creators who built the platform to begin with.

Or is it?

If I’ve learned anything in the Internet age, it’s that Big Tech finishes first — and then murmurs how tired it is, rolls over, and falls asleep in two seconds flat while you lay awake on the wet spot.

Instagram is competing with TikTok and as Facebook’s stock rollercoasters south, the only way Zuck can continue lining August and Maxima’s trust funds is to keep you doom scrolling down your feed, so his ad revenue goes up.

Social media companies want you creating as much free content for their platforms as possible to boost their profits, not your brand.

You are the product.

Social media — scratch that, nearly all media — makes money off advertising.

That’s why Instagram is free! Zuck & Co aren’t providing a public service to us, they’re providing a big audience to advertisers who want the best chance of reaching buyers.

And now with its new “Favorites” feature, Instagram is delegating its work to you. When you designate someone a “favorite,” you’re telling the platform which accounts are most profitable for them.

When we long for the “bygone days” of Instagram, when our content was seen by a larger percentage of our audience, we’re not longing for the chronological feed. We’re longing for a less saturated, less monetized platform, with fewer creators to compete with.

The switch to an ad-soaked experience is not a function of social media suddenly selling its soul. This is the business model. Want to be the next Fuckerberg? Build a platform, attract users, addict them to your tool, then slap those metrics on a slide deck and watch the advertisers fight over whose butt pee tea goes first.

A return to the chronological feed does NOT mean we’ll see MORE from our favorite creators, but MORE from the creators who create MORE.

They are training us to be as prolific as possible, not because it’s what’s best for us, but because it’s what’s best for THEM.

We’re doing unpaid labor for Mark Zuckerberg. And the most troubling part is, he’s convinced us that it was our idea.

I shared these thoughts on Twitter — another ad-driven media tool — and an interesting conversation followed in the comments.

“But it goes back to an age old controversy of quality over quantity. Quantity does and will matter,” content marketer and agency owner Steven Burkhart responded.

“But who does it serve?” I asked.

“That’s a great question...I would ask: what does it look like to have VAST quantity and just enough quality to get people to a place of value (aka your own platform) since that is the ultimate goal either way?” he replied.

“I get stuck on VAST quantity because that is ultimately what drives ad revenue, where we are doing unpaid labor for platforms that will only demand more and more and more…when we ALL produce more and more and more VAST quantities of content with 'just enough' value to get folks over to a platform we control, knowing that so many people DO spend a large amount of time on social, what is the culture we are creating here BEFORE they click? I think there are cultural consequences to us being forced to participate in the buying and selling of attention this way. At a time where folks see up to 10,000 ads per day, this is reshaping our humanity, our capacity for complex discourse, our tolerance for nuance…” I thumbed back from my phone.

And this next part is why marketing needs muckrakers!

“I think as long as we use the platforms we have to play by their rules if we expect success. If it begins violating our morality then I guess it’s time to find another job," Burkhart responded before he left the thread.

“I’m walking that very tightrope between brand strategist (my job) and cultural criticism (my side hustle haha). I think the industry needs that hybrid of folks who want to help small businesses without becoming apologists for harmful systems, ykwim?”

The conversation ended here.

I hearted my last lonely tweet, which is very uncool, but I did it anyway because the thought deserved some love.

For years, I wrestled between recognizing the harms of brand culture and “playing by the rules” because that’s just what you do.

This fellow agency owner speaks to how we’re told to respond when we recognize harm in any industry or system, not just marketing: “Hey, I don’t make the rules! Got a problem with how things are run? There’s the door…”

What happens when all the critics leave? What happens when there are no marketing stakeholders left willing to “plumb the depths of the problem” as Anand Giridharadas puts it in Winners Take All? And where does “the door” you’re pointing me towards go exactly?

Social media is no longer a niche operation populated by a few college kids poking each other and plowing into their friends’ walls with the BeAuTiFuL TrUcK.

Today, at least 7 in 10 Americans use social media, according to the Pew Research Center. (And at least half get their news there.)

Social media is so central to how we live today, it has the power to influence our election results, recruit millions into QAnon, shape public policy — the list goes on.

And when it comes to marketing in general, the average American sees up to 10,000 ads per day. Advertising is woven into the fabric of our culture; it fuels the engine of consumer capitalism.

If there was a clearly marked exit, we’d be trampling each other like Black Friday zombie shoppers to get to it.

“If it begins violating our morality then I guess it’s time to find another job,” is a pretty bold statement that, at its best suggests there’s somewhere to go to easily escape these harms, and at its worst ignores that simply switching jobs when we don't agree with industry practices is not an economic reality for most people — me included.

And the overlying premise is that criticism is unwelcome here.

Get with the program or get out.

In Episode 6 of the Marketing Muckraking podcast, “Why are there no negative B-School reviews?” I discussed the reasons why so many celebrity coaching programs have a noticeable dearth of negative feedback.

The fact that, in B-School’s case, Marie Forleo’s 65,000+ customers agree to a dubious non-disparagement clause when they purchase is one main reason.

But the other reason is reflected in this Twitter thread: social pressure to “go with the flow” and avoid being seen as a squeaky wheel, lest you RKA your reputation and end up on the industry’s naughty list.

The consequence of there being no negative reviews on industry-leading programs is that students who feel disappointed with $2500 purchases, who don’t achieve the results they expected, even after putting in the work — or who never would have made the purchase to begin with if they had access to diverse viewpoints before cracking open their wallets — look around to see if others share their experience and receive the message that they are alone.

Wiping any trace of negativity from the Google record is a special type of gaslighting that leaves people feeling that their results are an anomaly, when in the reality of celebrity courses and the volume they rely on, mediocre results are the rule.

It’s even written in the fine print, buried below the dozens of glossy testimonials! Results not typical.

This is how I’ve felt hiking the steep bluffs of branding all these years — if no one in this industry is critiquing the harm that marketing causes, maybe the harm isn’t there? Maybe it’s in my head? Maybe I should get with the program. Shut my mouth and market.

Oh hey, burnout! I didn’t see you there! Were you hiding behind that bluff? Don’t mind me while I burn it all down.

This is why marketing needs muckrakers.

What is a muckraker?

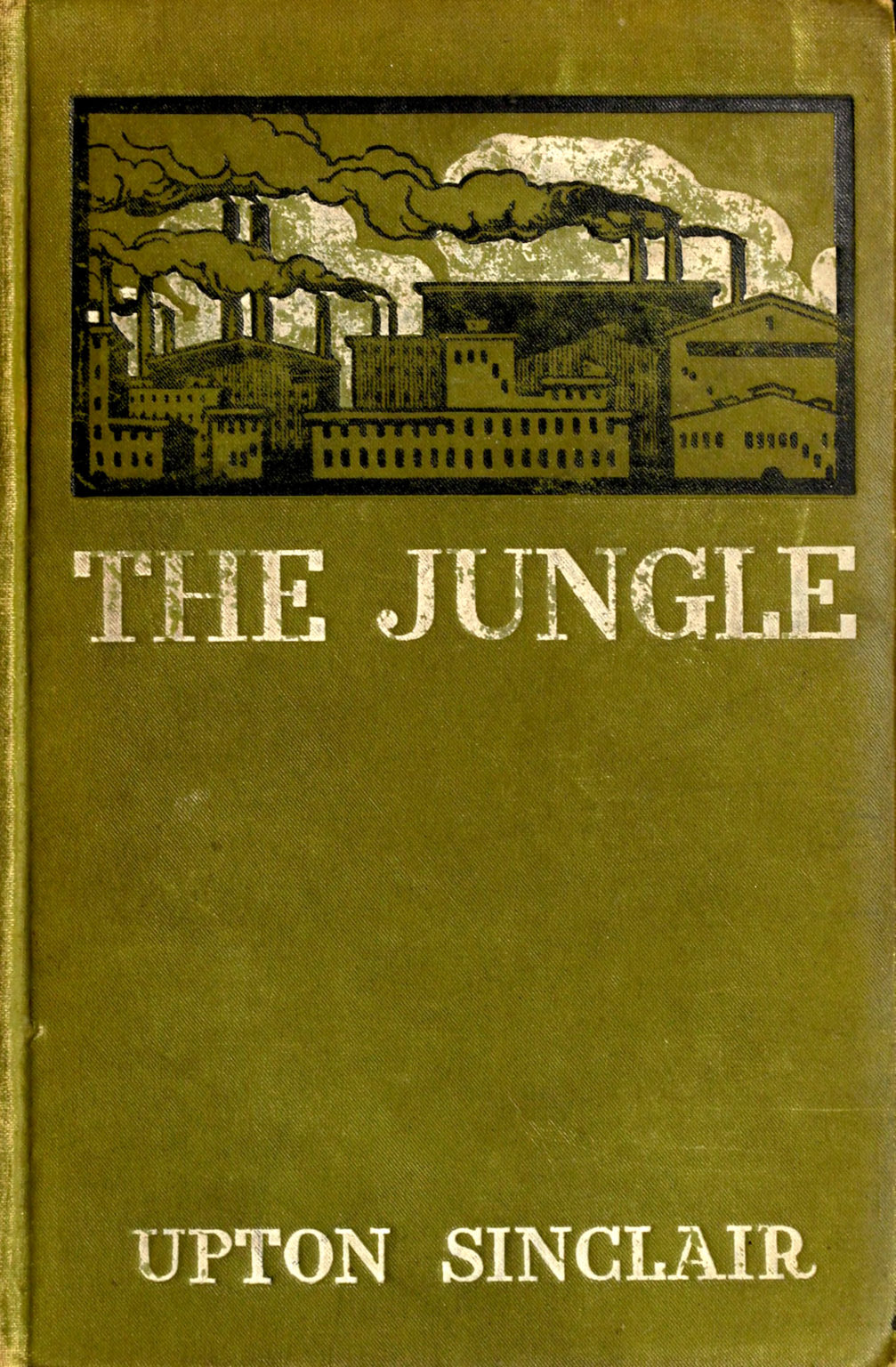

The term originated with pre-World War I writers like Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens, and Ida B. Wells, who exposed social and economic injustices during the Progressive Era (1880-1920). Muckrakers often found outrageous ways to make their points, earning them a scandalous reputation. But their work is responsible for many of the worker and consumer protections we take for granted today.

Until The Jungle hit the presses, most Americans had no idea what happened behind the scenes of the meat-packing industry, how fiercely businesses fought to block unions, or how low wages kept people trapped in poverty.

The capitalist elite, reliant on the machine age and factory labor to make consumer capitalism profitable within the USA, worked hard to distract the public from the harms of industrialization.

Through their efforts, industry transformed America into the first economy in the world to depend on mass production.

Before muckrakers, the ad-driven media focused primarily on all the “freedom” and “choice” mass production offered Americans. This coupled with the rise of “mind cure” culture, an ideology that one could think their way out of their worst problems and the predecessor to today’s choose to be happy toxic positivity, obscured how little freedom consumers had in this new economy.

Muckrakers reintroduced the examination of widespread injustices, corruption, and abuse of power back into the national conversation, raising public consciousness, and ultimately bringing about legislation that protected workers and consumers.

In today’s Internet age, social media has made writers of all of us.

You don’t need to be a journalist to be a muckraker anymore. You simply must have an eye for social and economic injustices and a willingness to rake the muck to find the truth, which is a fancy way of saying “shit stirring.”

Now, I’m not comparing myself to Upton Sinclair here in my shit stirring about B-School and the industry that surrounds it, but I’m inspired by the work of these writers to look beyond the glitter of the Gilded Age and question the status quo, however unpopular.

If marketing fuels the engine of capitalism, the source of most modern problems, then this industry and its “rules” need constant examination.

It’s not enough for this criticism to live buried within academia, where the masses — and my audience of small business owners and creators — rarely trod.

Just as advertisers and mainstream journalists of the Progressive Era painted a picture of mass production begetting a utopian paradise of choice, where everyone was “free” to buy whatever they wanted, restricted only by their capacity to think their way out of their problems, today’s ad-driven media and the marketing it rides in on rarely questions what brand culture is doing to us.

Consumers and creators alike are left with the fallacy that the solution to our problems lies squarely within the capitalist infrastructure.

Or that maybe the problems we see aren’t really there to begin with, because why else would so few be addressing them?

And if you happen to work in marketing like I do, the prevailing sentiment is to “play by the rules” or “find a new job,” as my Twitter conversation reinforced. This means the industry conversation is dominated by apologists, less concerned with how “the rules” of marketing lead to exploitation and injustice, than how to best leverage these rules to get their piece of the pie.

The difference between now and then is that, at the time when early muckrakers were writing, the powers that be were actively manufacturing a buying public.

Businesses had to train people to buy constantly and equate consumption with self-actualization.

Before mass production, the United States was largely an agrarian and handicraft economy. People didn’t buy things as much as they made them. And if they absolutely needed something they couldn’t produce themselves, they went to someone they knew locally to make or grow it for them.

The captains of industry at the turn of the 20th century would have walked through fire (inadvertent Tony Robbins joke?) to have access to a consumer public as eager to buy as we are in the 21st century. Where we proudly associate the branded products we own with our identity and values. And funnel our activism into “voting with our dollars” while we wait for corporations to do the right thing.

And while today’s average American sees as many as 10,000 advertisements/day, 100 years ago, you might see only a handful. None if you lived in rural America and didn’t read the newspaper.

Bringing this back to Fuckerberg & Co, when it comes to mass media, the public has always been the product. That’s nothing new.

But unlike the Progressive Age, where the public’s attention was sold to advertisers to make newspapers — and then radio and then television and so on — profitable, in the Internet Age, we are both the product AND the producers.

Churning out constant content in hopes of being seen by a tiny fraction of our audience. It is our contribution to social media that makes it a tool worthy of advertising. We are doing unpaid labor and thanking the puppet masters who created these platforms for the opportunity.

Marketers position social media platforms as our benevolent allies, whose rules we must abide by to be rewarded with success.

And while it may be true that modern businesses struggle to succeed without playing the social media game, the simple fact that our culture and economy have shifted to make something indispensable, does not make it above reproach.

Academics and journalists have valuable viewpoints.

But there’s something about wading in these waters every day, building brands and businesses in the Internet age, while walking the tightrope between making money and making change, that makes our insider perspective invaluable.

Marketing needs activists now more than ever.

Marketing needs muckrakers.

Will you join me?

Let’s stir some shit up.

Sources for this essay include:

-

Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture by William R. Leach

-

Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of the Consumer Culture by Stuart Ewen

- Satisfaction Guaranteed: The Making of the American Mass Market by Susan Strasser

p.s. Sick of business newsletters that have all The Answers™? Well, I've got nothing but questions. For more marketing muckraking and brand strategy gone wild, sign up for my emails here:

If you liked this, read on:

In many ways, it seems easier to become a “personal brand” version of yourself than to be yourself. Brands are built on simplicity. A “good”…

Read More...Rebrand TOO MUCH to SO MUCH. Instead of saying, “She’s TOO MUCH,” say, “She’s SO MUCH.” You’re welcome. Lessons on burning it all down…

Read More...In 2021, I started a business / art experiment called FREE SCHOOL. I didn’t know at the time that this school would teach me to free myself. What happens after you burn it all down?

Read More...